Hogarth may have warned against the dangers of ‘mother’s ruin’ in his famous print, but a century later, in stark contrast, Hodge’s gin saved lives. This is the story of the, now undeservedly dusty, Victorian industrialist, gin distiller and fire hero: Captain Frederick Hodges. We tend now to take for granted the cosy security blanket of the London Fire Brigade, knowing that if we are over zealous with our scented candles we are a short phone call away from safety. Go back a few hundred years and there was no such thing as a ‘999 call’, or even a public fire brigade at the end of the line, had telephones existed. Londoners without means were left to burn, whereas affluent folk bubble-wrapped their homes with insurance and were given a plaque, such as that shown below, as proof of purchase (treat yourself to a wander around the City one day, look up quite a lot and you’ll probably see some).

It was a far from perfect arrangement: if the insurance company’s brigade arrived on the scene to find the fire was at an un-plaqued neighbour’s abode, the flames would be left to ravage the entire block. This set-up clearly couldn’t last, and it didn’t; eventually, in 1833, the various insurance brigades clubbed together and formed a larger fire army: the London Fire Engine Establishment. The LFEE kindly put out fires at properties that weren’t insured – provided they were threatening the ones that were, of course. Those with large businesses went a step further and created their own brigades, and that’s where the juniper comes in.

Known as a ‘sweetened cordial gin’, Hodges’ was the Gordon’s of its time, and was sold across London and beyond. Popular ballad writers even immortalised it in song, with three long stanzas devoted to its effects:

‘The Gin! the Gin! Hodges’ cordial Gin!

It fairly makes our head to spin:

It gives us marks, and without bound,

It turneth our head completely round;

It plays with our eyes, it mocks our brain,

And sends us rolling in the drain…’

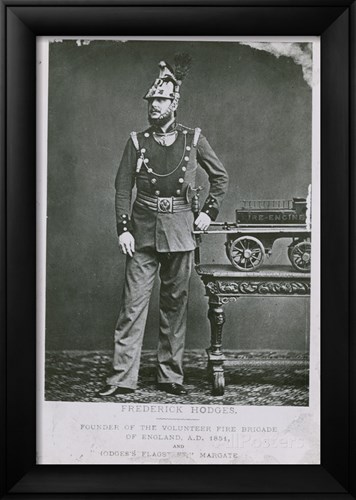

Having inherited the Lambeth road distillery where he was born, Captain Hodges had premises to protect – he was neighboured by factories for fireworks, tallow and candles and this, coupled with his zest for technology and vigour for fire prevention, led to him establishing the biggest and best brigade in the Capital. To begin with, he choked flames locally in Lambeth, but Fred’s interest in blaze-snuffing soon extended further and he decided to erect a lanky ‘observational tower’ at the distillery so that he could send out his response in lightning time. Fred was delighted with his mast, with its side effect of spectacle, and he proudly stated that it: “became at once an ornament for miles around and on high days and holidays waved a Union Jack, 30 feet in the hoist and 60 feet in the fly.”

The response time of Fred’s engines became infamous in the borough and rival brigades were flummoxed with how he always managed to pip them to the post, claiming the monetary reward for being first on the scene. His fervour for fire could not be extinguished and he poured a plethora of pounds into the latest technology, developing steam engines to improve his fleet. Grateful locals pooled donations for a gift to honour him and he requested a new, ostentatious, fire engine – complete with all the latest bells and whistles. The spectacular result – inscribed with a thank you note for: ‘his heroic and unparalleled exertions to protect life and property from fire’ – is, luckily for us, now preserved in the Museum of London.

Though impressive, Fred’s fleet could not keep pace with the chaotic industrial expansion of the city, even if it was his responsibility. The Government had thus far slept through the growing need for a more effective solution but, in 1861, they were stirred by a gigantic blaze. Starting on Tooley street and lasting two days, the flames cascaded across a quarter of a mile of the South Bank; people flocked in droves on bridges and boat to feel the heat on their cheeks and marvel at the orange glow of the river.

Fred’s and other brigades battled hard but the fire fought back, killing James Braidwood, the much respected leader of the LFEE, in its path. Now awake to the problem, the government formed a select committee and eventually, in 1865, parliament passed ‘an act for the establishment of a fire brigade in the metropolis’ and so was born the London Fire Brigade: putting out flames and rescuing cats, regardless of the state of their owner’s bank account, ever since.

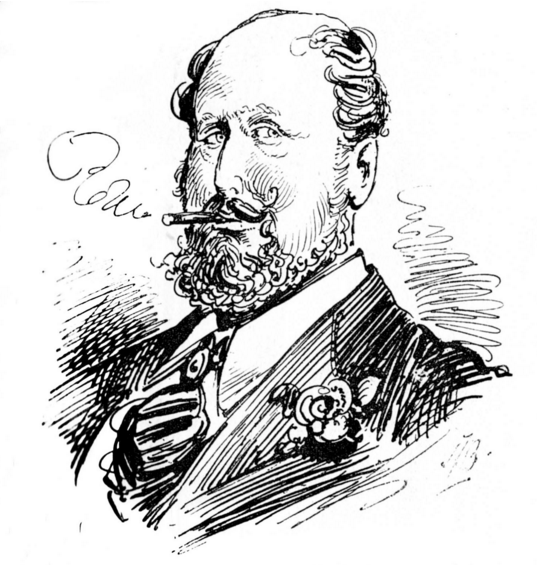

In the following years Hodges’ gin became no more, the distillery was taken over by a firm called Daun & Vallentin’s and Fred made a permanent move to his Margate country pile. It seems that he continued to court the limelight there – building, yes you guessed it, a huge flagpole – complete with access bridge for likeminded flag enthusiasts. Local residents have later referred to him as ‘a bit of a nutcase’ after a series of escapades in which he caused carnage on the streets of the quiet seaside town: riding his steam carriage whilst persistently sounding his whistle and bumbling into the street furniture. The below caricature of him in later years goes some way to capturing his impudence.

Hodge’s ballad and commemorative fire engine are cinders, quietly glowing to remind us of Captain Fred’s story, but he is still something of an unsung hero. Maybe you’ll think of him with a small salute next time you’re sipping on a G&T, passing one of the growing number of new independent London distillers, or even waving a flag.