‘Early modern people lived in great darkness… in the seventeenth century consumer demand for window glass, mirrors, candles, and oil lamps all accelerated notably.[1]’

In terms of important advances, a lot of weight is often put on the Victorian invention of electricity and the dramatic effect it must have had on the atmosphere within our homes. After all, what better conjures a feeling of the past then a power cut? – giving us a chance to stack up the candles and enjoy their orange-hued flames flickering glitter onto our walls.

A less obvious advancement in the lighting of our homes came earlier: with the increased availability and affordability of plate-glass mirrors in the late seventeenth century. Prior to this, these wall-expanding and light-reflecting marvels were rarities found only in the houses of the elite.

In the years 1675 to 1725 mirrors listed in probate inventories of the middle classes increased from 22 to 40%.[2] The example pictured above is typical of the sort of glass you may have found in such a home by this time. The frame is humble in design, with olive-wood veneer making up its moulded cushion-shape and the only possible embellishment hinted at by two holes at the top, showing a potential for a cresting similar to that shown below. English-made, modest-sized and with a humble wooden-frame, it would have made a firm statement of ‘politeness and gentility’ of which visitors to the home would have approved.

For many years the Murano craftsmen at Venice had monopolised the looking-glass industry by closely-guarding their silvering and casting techniques, mirrors were expensively imported luxury items for display only in the very finest of households.[3] By the late seventeenth century, migration resulted in these craftsmen bringing their skills to the rest of Europe, who imitated and improved on Venetian methods. France was one of the first to make pace in refining the casting technique by ‘pouring molten glass onto an iron plate covered with sand, which was then made smooth before the annealing process[4]’. This enabled the creation of much larger sheets of mirror than had so far been possible. Previously, English production lagged further behind and had been restricted to an ‘output of small, often poor quality, mirror-plates.[5]’ If they had mirrors in the home at all, ordinary English folk used ‘polished steel’ specula ‘which were imported in quantity throughout the seventeenth century.[6]’

An important turning point was the creation of ‘The Worshipful Company of Glass Sellers’ which received its Royal Charter in 1664 with the purpose of dictating fashion and exercising ‘control over flint glass production and glass imports[7]’ as well as funding research into techniques[8]. In the same year, the Company imposed an import ban on all foreign glass. The ban was short-lived, being lifted in 1668, but its few years-worth of influence meant that a healthy homegrown glass-making industry was established, with 709 apprentices registered between May 1665 and June 1739.[9]

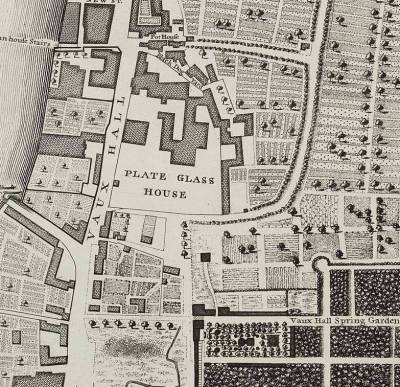

Around this time George Villiers, the second Duke of Buckingham, was granted a patent for his mirror glass technique and the creation of his industrious glass house at Vauxhall greatly advanced the English industry’s reach and reputation. His adverts exclaimed that:

‘Large Looking-glass Plates, the like never made in England before, both for size and goodness, are now made at the old Glass House at Foxhall known by the name of the Duke of Buckingham’s House, Where all persons may be furnished with rough plates from the smallest sizes to those of six foot in length, and proportionable breadth, at reasonable rates.[10]’

Coinciding with this increased manufacturing noise were changes to room functions within the home. For instance, according to Lorna Weatherill, the parlour, ‘formerly a best bedroom with some seating and storage, became a best living room, containing decorative things and new types of furniture.[11]’ This opened up a space for novel new objects to add to the pleasing aesthetics of the most visited room in the home. Aside from decorative merits, light reflection was an important additional benefit. With limited and expensive light from candles, as well as fewer windows thanks to the 1696 tax, mirrors were an effective way of extending light to extinguish some of the gloom and provide a warm welcome to guests.

Of course another benefit I haven’t mentioned is vanity. It must have been quite a shock to look into a well-polished and perfectly reflective mirror for the first time. I imagine it would have been a bit like the transition from SD to HD television when suddenly a whole wealth of pores and blemishes were visible. I can’t help but wonder if the increase in mirror-ownership in the early eighteenth century might be a contributing factor to the increase in dandy foppishness by the century’s end? I’m sure there’s a follow up post on the history of vanity to be found here, watch this space!

[1] De Vries, Jan. The Industrious Revolution. New York, Cambridge University Press, 2008

[2] Weatherill, Lorna. Consumer Behaviour and Material Culture in Britain, 1660-1760. 2nd ed. London, Routledge, 1996

[3] Klein, Dan & Lloyd, Ward. The History of Glass. London, Orbis, 1984

[4] Edwards, Clive D. Eighteenth-century Furniture. Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1996

[5] Child, Graham. World Mirrors, 1650 – 1900. London, Sotheby’s Publications, 1990

[6] Bowett, Adam. English Furniture – 1660-1715: from Charles II to Queen Anne. Woodbridge, Suffolk, Antique Collector’s Club, 2002

[7] Berg, Maxine. Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2005

[8] Liefkes, Reino. Glass. London, V&A, 1997

[9] Tyler, Kieron & Willmott, Hugh. John Baker’s Late 17th-century Glasshouse at Vauxhall. London, Museum of London Archaeology Service, 2005

[10] Advertisement in The Post Man, 1700. Cited in Wills, Geoffrey. English Looking-Glasses: a study of the glass, frames and makers (1670-1820). London, Country Life, 1965

[11] Weatherill, Lorna. Consumer Behaviour and Material Culture in Britain, 1660-1760. 2nd ed. London, Routledge, 1996